DongKyun Kang moves from mentored to mentor

Changing the course of early careers

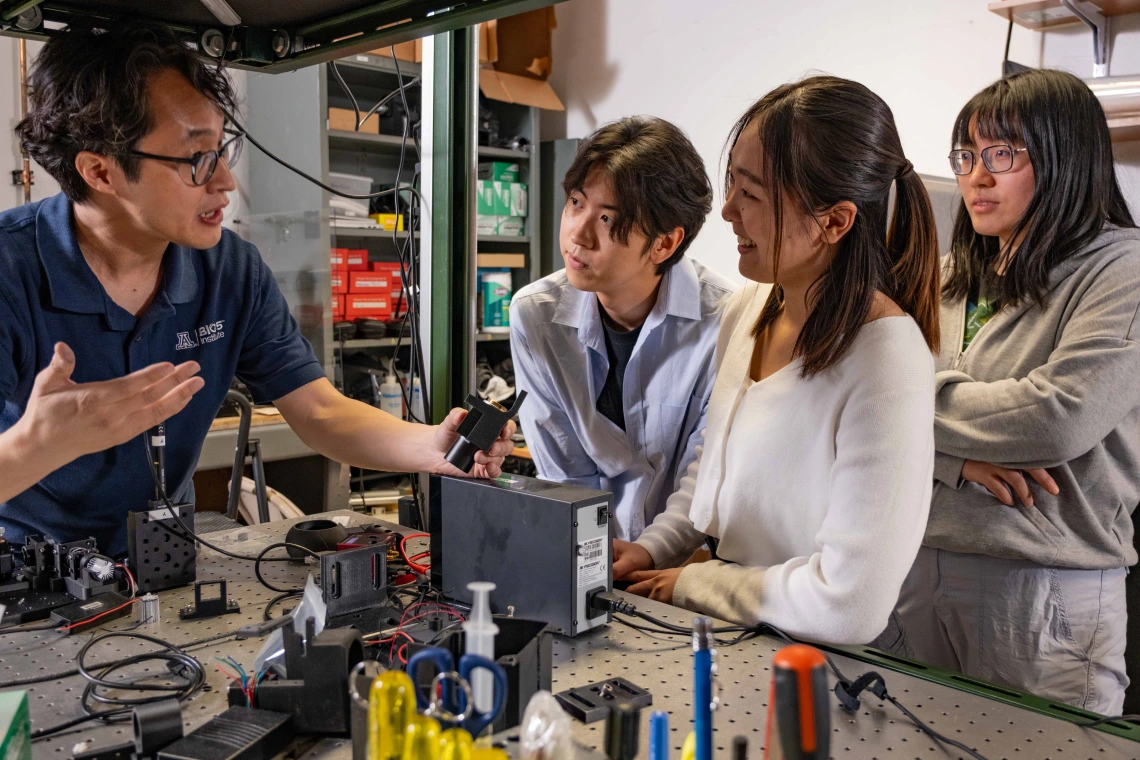

In his windowless, garage-sized lab in the University of Arizona Wyant College of Optical Sciences building, DongKyun Kang, PhD, meets with his students daily to make sure they are on track with their projects and, most importantly for them, feeling confident in their training.

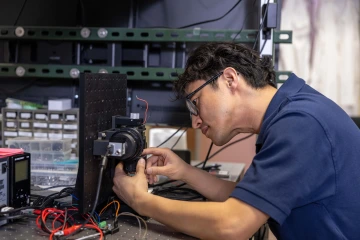

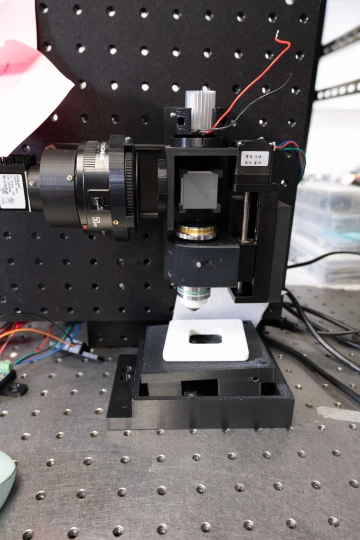

A consummate professor with an easy smile, Kang, a U of A Cancer Center member and associate professor in optical sciences, biomedical engineering and the BIO5 Institute, works with his students to design and create each of the handcrafted instruments lining the lab’s hydraulic table.

“In our lab, it's like one big supportive family,” said Jingwei Zhao, a doctoral student from China, who is in the U of A College of Optical Sciences. “The atmosphere is super friendly and healthy. We collaborate on projects, help each other out with research questions, and share our expertise in areas like optics, mechanical design, electronics, coding, and public speaking.”

Kang has volumes to teach his students in microscopy that he gained through his NIH-sponsored projects on developing smartphone confocal microscopy devices for skin and cervical cancer diagnosis both in Uganda and at home in Arizona.

“For every technology or device that my lab pioneered in the field, there is a team of dedicated students,” Kang said. “My students do awesome jobs developing affordable optical imaging devices for medical applications. They cover the entire spectrum of device development, ranging from concept design, optomechanical design, software development, building and testing, and finally clinical testing.”

Transforming a career through mentors

After earning his doctorate in mechanical engineering from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Kang followed his training and began developing microscopy for inspecting semiconductor devices and professional displays for screens and other electronic equipment. But he found his career path just wasn’t quite right.

“After I graduated from my Ph.D program, I felt that I wanted to work more toward actually helping people,” he said.

He met his mentor, Guillermo Tearney, MD, PhD, from Harvard Medical, at a conference. Tearney invited Kang to join his lab as a postdoctoral fellow.

Kang switched to biomedical optics and joined the Tearney Lab at Massachusetts General Hospital. His first project was to develop a device to diagnose esophageal cancer.

“We made this very unique endoscope, that can go into the patient and take images of cells from the patient without taking the tissue out. That was really exciting,” Kang said.

He then started an independent project looking into using microscopy techniques to improve lumpectomy surgery for breast cancer and surgeries for skin and other cancers. Using the smartphone-based microscope to examine patients rather than a biopsy allows for an early and accurate diagnosis, especially in rural areas. He said it also allows clinicians to monitor the patient’s treatment as it progresses.

The long road to smartphone use for confocal microscopy

Kang said that the smartphone-based confocal microscope idea came to him through his degree studies.

“One beautiful day back in Boston, Massachusetts, I was taking a shower, and it just came to me that one of the ideas that I had when I was a graduate student can be useful in developing a smartphone-based microscope that can be used in all different settings,” Kang said.

He said he received mixed responses when he discussed it with clinicians. One clinician who was excited was Esther Freeman, MD, PhD, the director of Massachusetts General Hospital Global Health Dermatology and an associate professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School. Freeman has a Global Health Dermatology program and an ongoing collaboration with Ugandan collaborators.

They began collaborating on developing their now patented Smartphone-based Confocal Microscope that they use to image suspicious lesions in Uganda.

“Since HIV-positive patients tend to have a compromised immune system, they tend to develop cancer more often,” Kang said. “So that's why a particular type of skin cancer called Kaposi sarcoma and cervical cancer are big problems in Uganda.”

Kang said that when he first moved to UArizona, he began looking for an expert in skin cancer to form a collaboration.

“It just so happened that we have the world's expert on skin cancer, Clara Curiel,” Kang said. “Since then, we've been working together for more than six years, publishing papers together, and developing the devices together. It’s been very exciting.”

Kang is working on a pilot project funded by the UArizona Cancer Center’s Cancer Prevention and Control Program to develop an even more low-cost microscope device that can see melanocytic cells.

“Through this CPC pilot program, we are in the process of developing a new tool called a cross polarized microscope that can visualize individual melanomic cells,” he said. “We hypothesize that if we could visualize individual cells, they can be useful for something like chemoprevention of skin cancer.”

Empowering the next generation of scientists

According to Kang, though UArizona students are well-trained through their coursework, working in a lab with a professor is instrumental for their future.

“Applying knowledge gained from formal courses to solve biomedical problems requires iterative trials and failures,” Kang said. “Mentoring is critical in guiding students through this often-challenging process and encouraging them to come up with creative ideas.”

Momoka Sugimura, a doctoral student from Japan in the UArizona College of Optical Sciences, said that Kang once reached out to industry professionals to understand what qualities they seek in potential hires and shared these insights with his lab students.

“Dr. Kang is always proactive with career and project guidance,” she said. “He also involves us in discussions with clinical collaborators, which helps us understand the big picture of our projects. This experience is invaluable, as it prepares us for considering customer needs and other practical aspects in future industry roles."

Yong Jun Kim, a master’s student from Korea in the UArizona Department of Biomedical Engineering, said that having a strong mentor has been the key to his technical growth.

“In my work, Dr. Kang always tries to provide constant feedback, which is critical for refining my image analyzing process and lens design,” said Kim. “The active discussion with him ensures that I am staying on the right track and meeting my research objectives effectively.”

Kang said he hopes his students leave with a strong background in problem-solving skills.

“I want them to be able to fully understand the given medical problem, translate medical needs into engineering specifications, develop a tool that meets the specifications, and evaluate it in clinical settings,” Kang said.