What Is Chemoprevention?

Chemoprevention lacks the name recognition enjoyed by chemotherapy, but the concepts behind the names are similar.

Whereas chemotherapy is a chemical substance that can act as a therapy for a disease, chemoprevention refers to a natural, synthetic or biological agent to prevent, reverse or suppress the first steps of cancer development. There are probably some chemopreventive strategies already on your radar: aspirin to prevent colorectal cancer, tamoxifen to prevent breast cancer, the HPV vaccine to prevent cervical and anal cancers.

The University of Arizona Cancer Center is renowned for its chemoprevention research. David Alberts, MD, UA Cancer Center director emeritus, established this stellar reputation with decades of clinical and translational research. Today, these efforts are buttressed by the UA Early Phase Chemoprevention Consortium, founded in 2003. This Consortium is one of five such programs in the nation sponsored by the National Cancer Institute to help support clinical investigations into promising chemopreventive substances. Over the years, it has brought millions of research dollars to the UA Cancer Center.

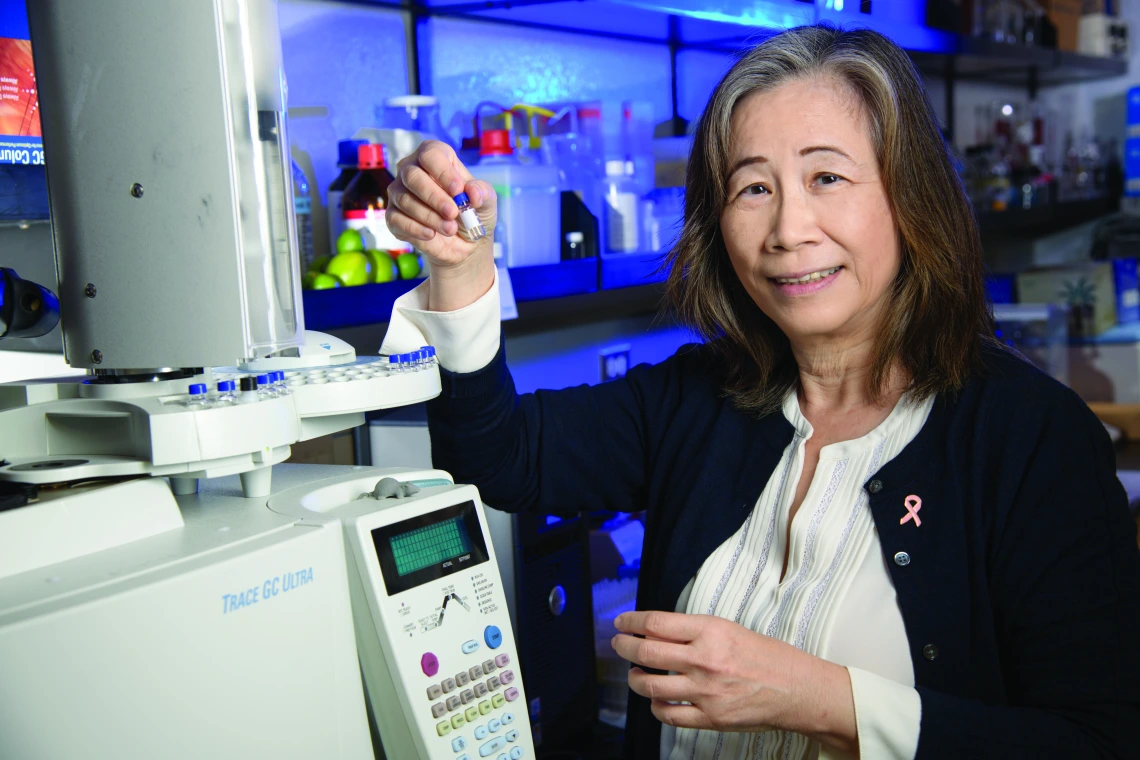

Directing these complex, yet crucial, explorations today is Sherry Chow, PhD, co-leader of the UA Cancer Center’s Cancer Prevention and Control Program. Additional collaborative teams of UA Cancer Center investigators have been funded through other sources to conduct clinical and translational chemoprevention research.

“It’s a very challenging task to develop a drug that can prevent cancer,” Dr. Chow says. “It can take years.”

Because the journey from normal tissue to invasive cancer can be stretched out over many years, it is difficult to follow a potential chemopreventive substance over time to assess how well it works.

“Definitive cancer prevention clinical trials are expensive and require long-term follow-up,” Dr. Chow says. “Compelling scientific and clinical evidence from rigorously designed early-phase clinical trials is critically needed prior to advancing an agent or agent combinations into large, definitive Phase III trials.”

To gather this necessary evidence, the UA Chemoprevention Consortium has conducted 17 early-phase cancer-prevention clinical trials. Investigators have examined agents running the gamut from pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals and vaccines, which were evaluated for their ability to prevent HPV-associated cancers and cancers of the lung, breast, prostate, skin and esophagus. Funding comes from a variety of sources, including from private donors whose support is vital to accelerating cancer-prevention research.

Dr. Chow especially is interested in digging into our diets for cancer-prevention clues. We know healthful diets are associated with reduced cancer risk, but we don’t know if we can isolate vitamins, minerals or other compounds from foods to prevent cancer. Early clinical trials into agents such as vitamin E and beta-carotene had mixed or even negative results — revealing just how difficult it is to untangle the intricacies of dietary patterns.

“A lot of those studies were based on observational data, but most people believe association studies don’t provide rigorous scientific evidence,” Dr. Chow says. “I think there’s still hope. We need to conduct prospective intervention trials to define the role of a dietary compound for cancer prevention.”

Kris Hanning, UAHS BioCommunications.

Sherry Chow, PhD (left), and Wade Chew, manager of the Analytical Chemistry Shared Resource, discuss laboratory assays to support cancer prevention clinical trials.

Foods are packed with thousands of chemicals, which can be present at varying concentrations and can be combined in different ways. The goal is to find the right doses and combinations that will converge to provide an extra level of cancer protection.

“Hopefully we’ll find a group of food — cruciferous vegetables, for example — that can be used to prevent cancer,” Dr. Chow says. “More studies definitely will be needed to confirm that.”

When life gives you lemons

Along with other UA Cancer Center researchers, Dr. Chow is involved in several projects investigating breast cancer prevention — including one study that seeks to unravel the potential anti-cancer properties of limonene, a component of an essential oil in citrus fruits.

“When you peel oranges or lemons, you get this oily feeling on your fingers,” Dr. Chow says. “That’s limonene.”

So far, scientists have had the most success preventing breast cancer with tamoxifen and raloxifene, powerful drugs that block estrogen receptors. But they can be pricey and come with side effects, making them worthwhile only for people at an especially high risk for breast cancer. But can those not at high risk protect their health with other substances — which preferably are safe and inexpensive?

Dr. Chow hopes limonene checks those boxes.

“Preclinical research has shown limonene has potential activity to prevent breast cancer,” Dr. Chow says. She has taken these early discoveries into human trials. “Our studies show that limonene distributes to the breast tissue and favorably changes the plasma metabolite levels associated with breast cancer risk. We’re excited about the findings.”

These trials were small, and did not compare women taking limonene to women who were not.

“Everybody received limonene, so we don’t really know whether these results were the true effect of limonene,” Dr. Chow says. “We would like to conduct follow-up studies to further understand

the role of limonene in breast cancer prevention. We need to compare people taking limonene to a placebo-controlled arm to understand whether it’s really working.”

An ounce of prevention

Everyone wants a cure for cancer, but finding effective ways to prevent tumors from forming in the first place is one of the UA Cancer Center’s most important missions. The UA Chemoprevention Consortium’s goal is to translate cutting-edge science into clinical breakthroughs.

“Chemoprevention is a field that needs more attention,” Dr. Chow says. “We still have a lot of work to do to develop an agent that can be well-tolerated, has a good safety profile and has a broad spectrum of activity, hopefully covering different types of cancer.”

Dr. Chow and her colleagues in the UA Chemoprevention Consortium are driven by a desire to lessen the tough toll cancer takes on patients around the world.

“I’m hoping that before I retire, I find something that can reduce cancer burden,” Dr. Chow says.

Your support for clinical trials at the UA Cancer Center helps us push vital research forward. To learn more, please visit uacc.arizona.edu.