National Cancer Institute Grant Will Support UA Cancer Center Researchers Investigating Lung Cancer Stigma

Lung cancer patients are more likely to experience depression, lower quality of life and reduced engagement in care. A UA Cancer Center team will test the effectiveness of a contextual cognitive-behavioral treatment in promoting coping tools to lung cancer patients.

Contact: Anna C. Christensen, 520-626-6401, achristensen@arizona.edu

Nov. 3, 2017

TUCSON, Ariz. – Two University of Arizona Cancer Center researchers have received a grant to spearhead a study to reduce stigma felt by lung cancer patients.

Heidi Hamann, PhD, UA associate professor of psychology and family and community medicine, and Linda Garland, MD, director of the UA Clinical Lung Cancer Program and associate professor of medicine, will test the effectiveness of a short-term intervention among lung cancer patients who report feeling a high level of stigma. The treatment is designed to help equip recipients with coping tools to overcome the self-blame and guilt often associated with the stigma surrounding lung cancer.

Dr. Hamann explained that their approach has “a focus on self-forgiveness and acceptance. People might get really stuck in feeling guilty and self-critical. We can help them feel unstuck, to move forward.”

In the study’s first stage, 10 lung cancer patients will receive the intervention in one-on-one sessions with a therapist. Their feedback will inform the second stage of the study, in which 20 lung cancer patients who receive the treatment will be compared to 20 lung cancer patients who do not. The approach will be evaluated for its association with reductions in stigma, depressive symptoms and anxiety, and increased quality of life. If the treatment appears beneficial, it would provide information for a larger study and facilitate implementation at cancer centers to better serve the needs of lung cancer patients.

Lung Cancer Stigma: Negative Judgment and Self-Blame

Because of the strong association between smoking and lung cancer, stigma surrounding lung cancer is shaped by the idea that the disease is “self-inflicted,” which can lead to feelings of guilt, self-blame and shame among patients, as well as judgment from others.

“A couple of different types of stigma exist. One is perceived stigma — the knowledge that other people may be treating them differently,” said Dr. Hamann.

“Some of our patients’ sense is that they’re looked down upon because they have smoked,” said Jill Mausert, RN, UA Cancer Center thoracic nurse navigator.

“When I was first diagnosed, the first thing out of everyone’s mouth was, ‘Oh, you smoked, didn’t you?’” said Beth, a UA Cancer Center lung cancer patient. “That kind of look, like, ‘You should have known better.’ To make me feel bad makes them feel better.”

The second kind of stigma, said Dr. Hamann, is called “internalized stigma, which is personal guilt. Feeling stigmatized may make patients feel like, ‘I don’t deserve treatment.’”

“It could cause people not to have as strong a will to live or be invested in their treatment,” said Jill Winter, LMSW, UA Cancer Center social worker. “It can feel like a heavy burden, like they’re being punished for what they did. It’s not productive for them to feel that way.”

Dr. Hamann said lung cancer stigma is “associated with poorer quality of life, higher depressive symptoms and impaired patient-provider communication.” Stigma also may add to the burden of illness when patients delay seeing a doctor when symptoms appear, fail to adhere to treatment or end treatment early. In addition, previous research has revealed that lung cancer patients who feel stigma may feel limited in their social support and reluctant to disclose their diagnosis to others.

“Patients who feel highly stigmatized may not share as much information with their family and friends,” said Dr. Hamann. “Social support is important throughout the whole process of being diagnosed with an illness like cancer. If you feel limited in that social support, that can have negative consequences.”

“As a medical oncologist for our lung cancer patients, I would like to understand how an undercurrent of stigma surrounding lung cancer may, in both direct and indirect ways, affect their clinical course,” said Dr. Garland. “Does stigma create isolation that may impact how my patients seek aid from friends and family, their ability to comply with a complicated treatment schedule, their facing the anxiety of scan results, and the long-term physical and psychological effects of being a cancer survivor?”

It is also possible that stigma contributes to the lower amount of research funding directed to lung cancer compared to other common cancers. In 2013, breast cancer received $13,532 in National Cancer Institute research funding per patient death, compared to $1,831 for every lung cancer death.

“That’s not to pit one cancer against another,” said Dr. Hamann — rather, it is a prompt for us to examine the reasons behind the disparity in funding, and how to increase the focus on lung cancer, which is the deadliest in the country.

Part of the stigma surrounding lung cancer, however, does “pit” cancer patients against one another. Beth spoke about the feeling that other cancer patients are “worthier” of living than she is.

“I had a friend who was diagnosed and died within three months. His wife was really struggling with trying to understand how I was still living and how he died,” she said. “When people die of another cancer, versus lung cancer from smoking, somehow it’s just not fair that you’re still alive and kicking, and other people aren’t.”

Stigma and Smoking History

Given the intense focus on behavior and the strong association between smoking and lung cancer, a divide may arise between perceptions of smokers and nonsmokers with lung cancer. Current (and even former) smokers often are thought of as “deserving” cancer and are more likely to experience feelings of guilt, shame and self-blame, while lifelong nonsmokers are often seen as blameless victims.

All lung cancer patients are at risk for stigma, however, regardless of smoking history.

“Nonsmokers know the perception of lung cancer,” said Dr. Hamann. “We interviewed nonsmoker patients who said, ‘When I tell people I have lung cancer I tell them I was not a smoker, because I know they’re going to treat me differently if I don’t say that.’”

Furthermore, perceived stigma could deter them from talking about their diagnosis in the first place.

“Maybe they don’t feel guilty, but they still don’t tell people about their cancer because they don’t want to deal with all the questions,” said Dr. Hamann. “Some people decide it’s not worth that burden.”

“It would have been healthier for me to expend my energy on other things, like trying to heal,” said Beth, the lung cancer patient. “I found myself explaining, ‘Yeah, I smoked, but I was 13. I only smoked when I was younger.’ It was very cumbersome, and that was the last thing that I needed to do, was have to explain myself. That takes energy and sometimes I just don’t have the energy to expend on that.”

Smoking: Never Too Late to Quit

There is no denying that smoking is a major risk factor for lung cancer. Even patients who already have lung cancer will reap benefits from quitting.

“Chemotherapy is more effective without the nicotine floating in the system,” said Mausert.

“Also, if you’ve been smoking, you don’t heal as well from surgery,” added Winter.

Smokers who are diagnosed with lung cancer are encouraged to quit. Unfortunately, health-care providers might need to walk a thin line between suggesting that patients quit smoking and arousing defensiveness for not being able to do so. Mausert explained that some patients feel providers are dismissive of how difficult it can be to quit smoking. A patient’s social network can also perpetuate this attitude.

“There may be situations in which family and friends will blame the person for their illness, especially if the patient continues to struggle with smoking,” said Dr. Hamann. “Family and friends might feel like the patient isn’t helping themselves, and might say, ‘Why can’t you just quit?’”

Additionally, health-care providers’ attempts to convince patients to quit can sometimes backfire as patients dig in their heels. Winter mentioned one lung cancer patient who, along with his wife, was a smoker: “They both said, ‘If one more person talks to us about quitting smoking, we’re not coming back.’”

Focusing on smoking as a modifiable lifestyle factor without acknowledging why people started smoking or how powerful addiction is overlooks the bigger picture.

“Obviously, smoking is a major cause of lung cancer, but there’s a lot of complexity in smoking,” said Dr. Hamann. “If we just focus on single behaviors we’ll lose our understanding of the complexity of illness.”

“If they’re older, in their 70s or 80s, many will say that cigarette smoking was glorified when they were younger and they started smoking,” said Mausert. “It was glorified many years ago in advertisements, in movies — the cowboys, the cool guy. It was also made to be sexy for women.”

Unfortunately, once they started, quitting was not necessarily easy.

“Smoking is an addiction,” said Dr. Hamann. “Some people have more resources to cessation than others. The more support we can give people, the better.”

Peter Jennings and Dana Reeve: Two Contrasting Cases

Dr. Hamann has a longstanding research interest in cancer patients, but was drawn to the stigma surrounding lung cancer around 10 years ago when the media reported the deaths of two celebrities very differently.

“The news anchor Peter Jennings and Dana Reeve, Christopher Reeve’s wife, died of lung cancer around the same time,” said Dr. Hamann. “I remember reading the articles about their deaths. In Peter Jennings’ case, they really highlighted that he had smoked. In the case of Dana Reeve, they made a point of saying that she had never smoked, that she had worked in nightclubs where there was secondhand smoke. In what other illness would there be such a major focus on the perceived cause, and how the person is then portrayed because of that?”

Dr. Hamann drew a parallel between lung cancer and AIDS. Early reporting often emphasized which HIV infections were transmitted through sexual contact and which were contracted by blood transfusions, setting up a dichotomy of “guilty” versus “innocent” patients. Viewing patients through a lens of guilt or innocence, however, does not help in their treatment or alleviating their suffering.

“Our goal as researchers and clinicians is to help treat and alleviate the suffering associated with the illness,” said Dr. Hamann.

Good health-care providers strive to deliver nonjudgmental and compassionate care.

“Our patients feel supported here,” said Winter. “Some patients have even said they feel like it’s a refuge. We have a clinic full of people who care about our patients. Everyone from the front desk to the phlebotomists, and of course all the nurses and the doctors, are so committed and caring.”

Drs. Hamann and Garland’s project, “An innovative approach to reduce lung cancer stigma,” is supported by a $100,000 National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant as part of its Basic/Clinical Partnerships to Promote Translational Research.

About the University of Arizona Cancer Center

The University of Arizona Cancer Center is the only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center with headquarters in Arizona. The UArizona Cancer Center is supported by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant No. CA023074. With its primary location at the University of Arizona in Tucson, the Cancer Center has more than a dozen research and education offices throughout the state, with more than 300 physicians and scientists working together to prevent and cure cancer. For more information: cancercenter.arizona.edu(Follow us: Facebook | Twitter | YouTube).

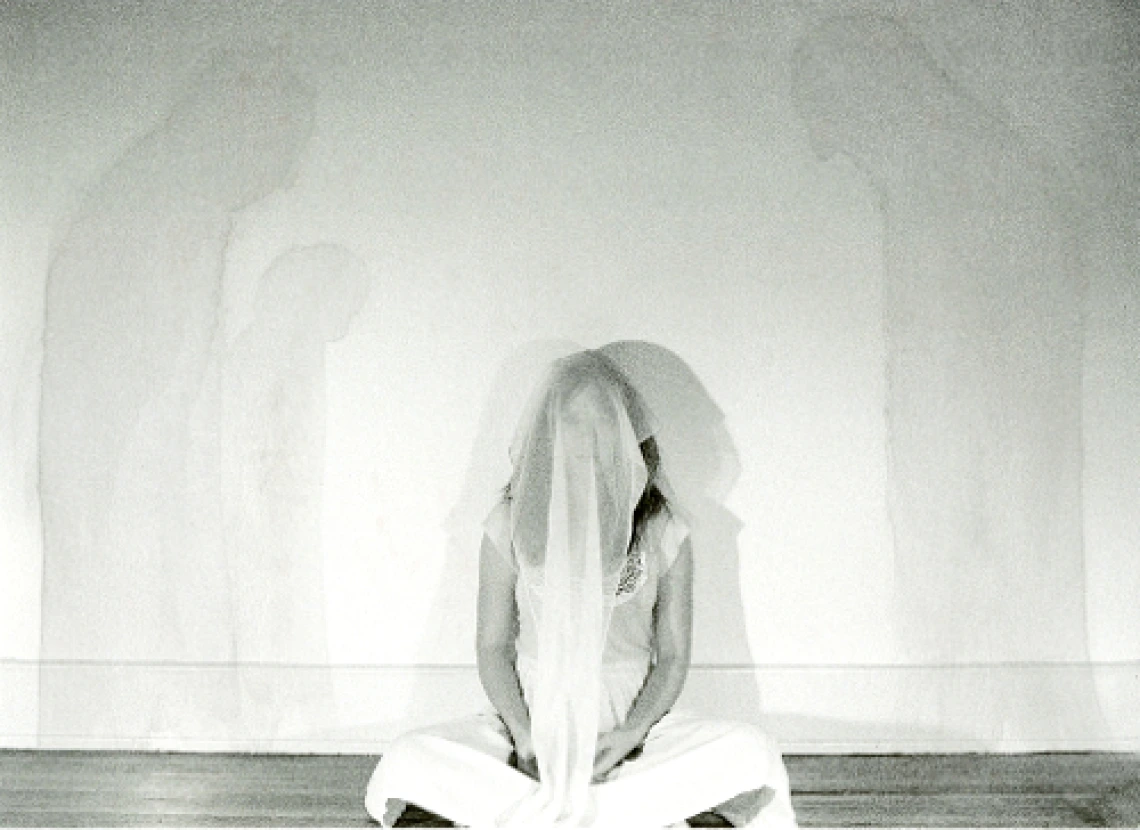

Image 1: “Stigma” by Katelin Reeser is licensed under CC by 2.0

Image 2: Heidi Hamann, PhD

Image 3: Linda Garland, MD