Skin Cancer Chemoprevention

Slowing, stopping or reversing a skin cell’s journey to cancer

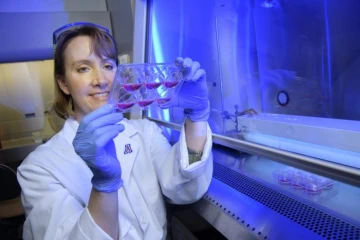

Clara Curiel, MD, is passionate about preventing, detecting and treating skin cancer.

In every corner of our state, the sun beats down on towering saguaros, gangly roadrunners and dry river beds. The sun’s ultraviolet (UV) rays are the primary cause of skin cancer, and although they are hard to avoid in Arizona, many steps can be taken to reduce skin-cancer risk.

Skin cancer falls into two main categories, depending on which skin cells are affected. The most common types of skin cancers, basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, originate from cells called keratinocytes. These cells produce keratin, the hard substance that allows your skin to act as a barrier between you and the outside world. The other type is melanoma, which originates from cells called melanocytes. These cells produce melanin, the pigment that colors your skin and protects it from UV radiation. Melanoma is rare but more likely to blaze a deadly path from its site of origin to other parts of the body.

Some of the nation’s best skin-cancer research takes place here at the University of Arizona Cancer Center, which houses the Skin Cancer Institute (SCI), a locus of patient care, research, and community outreach and education. One of the SCI’s biggest research foci is chemoprevention, the use of substances that can slow, stop or reverse the progression to skin cancer. The SCI team has been extremely successful in securing multiple National Institutes of Health grants over the years, including the Chemoprevention of Skin Cancer Program Project Grant, as well as additional research funding through the UA Chemoprevention Consortium.

When you think of skin-cancer prevention, you might envision yourself wearing a big floppy hat or slathering on sunscreen. But skin-cancer chemoprevention is a little bit different.

“Sunscreens include physical blocks,” says Clara Curiel, MD, clinical director of the SCI and leader of the UA Cancer Center cutaneous oncology team. “All they do is reflect, scatter and block the sun’s rays before they penetrate the skin — they don’t directly interact with the skin cells; they function as a filter.”

Sally Dickinson, PhD

“The goal of sunscreen is to prevent the initial UV damage,” adds Sally Dickinson, PhD, assistant professor of pharmacology at the UA Cancer Center and co-investigator on the Chemoprevention of Skin Cancer Program Project Grant. “In contrast, chemopreventive agents go to a damaged area of the skin and prevent it from progressing to cancer.”

Healing sun-damaged skin

Chemoprevention strategies can be employed at many points in time, starting when skin already has been damaged by UV radiation. Unfortunately, few products on the market fit this bill. But retinoids, derivatives of vitamin A that can be found in some over-the-counter skin creams, are one standout.

“Retinoids are known to slow down the progression of skin cancer,” Dr. Curiel says. “They help the keratinocytes recuperate from the damage caused by sun exposure. They also help with texture and pigmentation changes that happen with sun exposure, so you get that added benefit.”

Given how common skin cancer is, being able to lower your risk with an ointment or a daily pill would be a boon. But the catch is that any preventive measure must have an exemplary safety profile.

“Patients diagnosed with cancer frequently undergo a potentially toxic treatment, because the trade-off is justifiable,” Dr. Curiel says. “With chemoprevention, safety is a big deal. Not only should the candidate drug be effective, it should also demonstrate an acceptable safety profile since individuals are typically healthy and expected to be in treatment for an extended period for chemoprevention to be effective.”

Stopping cancer in its tracks

Skin cells take their first step toward cancer when they are unable to repair DNA damage and genetic mutations start to accumulate.

One strategy for treating skin in this “precancerous” stage is to target sun-damaged cells for destruction, using a technique called photodynamic therapy. First, a substance called aminolevulinic acid (ALA) is applied to the skin, where it is incorporated into the nucleus and metabolized by the cell. Then the skin is exposed to a specific wavelength of light, which the ALA is specialized to absorb.

“Damaged cells replicate faster and internalize more of the ALA,” Dr. Curiel says. “When you expose them to the light, cells with higher concentrations of the ALA will be more susceptible to the effect of energy released by light absorption. Almost selectively, the damaged cells are destroyed.”

Dr. Dickinson hopes to find more ways to slow skin cancer progression. Along with her colleague Georg Wondrak, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology and toxicology, her lab is working on a cream featuring a compound called resatorvid, an “orphan drug” that the manufacturer dropped when it failed to pan out in trials as an infusion for blood infections. Drs. Dickinson and Wondrak have found that, when formulated for topical use, resatorvid is much safer and might be effective in slowing down the progression of skin cancer.

“When we use it topically, we don’t see any toxicity,” Dr. Dickinson says. “Since we are pretty confident it’s going to be safe, we hope to use it longer term in sun-damaged areas to see if it blocks the progression of cancer.”

Resatorvid inhibits TLR4, or toll-like receptor 4, a surface protein on many cells. TLR4 can be “activated” by many factors, including UV light, setting off a domino effect that culminates in cell growth and division. When damaged cells are on the road toward cancer progression, however, activating TLR4 can hasten that journey — so, in theory, anything that can block TLR4 in a damaged cell can slow cancer progression.

In studies, TLR4 “went from low levels in normal skin to higher levels in squamous cell carcinoma,” Dr. Dickinson says. It’s possible that too much TLR4 increases inflammation, which is a factor in the development of cancer. Although inflammation is a normal part of the immune response, in which the body fights against injuries or infections, chronic inflammation can damage tissue and DNA, laying the groundwork for tumor formation.

“Resatorvid is attractive because it’s small enough to get inside the cell, and actually targets TLR4 and blocks its activity,” Dr. Dickinson says. “In mice, the topical application of resatorvid can block UV-induced skin cancer, so our next goal is to push it into the clinic to see if it hits the target in human skin.”

Protecting the whole body

Topical creams — like ALA, and perhaps in the future resatorvid — can be applied to parts of the skin with the most UV exposure, protecting individuals from nonmelanoma skin cancers like squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas.

“Nonmelanoma skin cancers appear in the areas of most sun damage: your face, your ears, your scalp, your neck, your hands, your arms,” says Dr. Curiel. “It makes sense to deliver a chemopreventive agent through a topical product — you know where to apply it.”

But melanoma, the most dangerous type of skin cancer, can arise in parts of the body that have had very little sun exposure.

“You don’t know where melanoma is going to develop,” Dr. Curiel says. “The most common site for melanoma in men is on the back, and on the legs in women. You’re not going to apply cream everywhere on your body to prevent a melanoma. So, the question is, is there a safe and effective drug you can deliver systemically, preferably in an oral formulation?”

A pill to reduce risk for skin cancer could deliver protection throughout the body, in a way a cream never could. In recent years, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs, have attracted attention for their possible role in skin-cancer prevention. Earlier in her career, at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center, Dr. Curiel pioneered a landmark study revealing this potential connection and completed the only randomized clinical trial evaluating NSAIDs in patients at risk of developing melanoma.

Because aspirin has been studied for so many other uses, many researchers have been able to make connections between aspirin and reduced skin-cancer incidence, but some studies found no association while others did. Another NSAID, celecoxib, also has seen mixed results, with a few studies finding decreases in basal cell carcinomas.

“There is still some debate,” Dr. Curiel says. Robust studies must specifically be designed to assess the relationship between NSAIDs on melanoma risk. Dr. Curiel, along with Sherry Chow, PhD, co-leader of the UA Cancer Center’s Cancer Prevention and Control Program, is preparing for a clinical trial that will investigate the potential of two NSAIDs, aspirin and sulindac, to reduce the likelihood of melanoma in patients whose atypical moles put them at a higher risk. Studies like these are necessary to help settle the debate over NSAIDs once and for all.

Sally Dickinson, PhD, hopes an "orphan drug" called resatorvid can slow down the progression of skin cancer.

Welcome to Arizona

Both Drs. Curiel and Dickinson hope more people will start to take sun safety seriously, especially in sun-drenched states like Arizona.

“I was listening to the radio this morning and they said it’s amazing how few people smoke these days,” Dr. Curiel says. “What I’m hoping for Arizona is that exposure to significant sunlight becomes like smoking — people just don’t do it.”

We can start by instilling healthful habits in children.

“Kids should be strongly encouraged to have hats on when they’re outside,” Dr. Dickinson says. “That should be a no-brainer.”

The SCI includes community outreach in its mission, providing sun-safety training for students, educators and health-care professionals. These efforts are fueled in part by donors, whose gifts to the Skin Cancer Prevention Friends (SPF) support research, community education and public sunscreen stations.

You have a range of options when it comes to preventing skin cancer — and future scientific advancements will only expand them. You can use sunscreen, wear protective clothing and avoid the sun to prevent your skin from being damaged in the first place. Once the damage has been done, you can use chemopreventive agents to slow down cancer progression. Beyond that, you can regularly see a dermatologist, who can catch skin cancer in its earliest and most easily treated stages. By learning how to protect yourself, you can live in harmony with the environment, enjoying the natural beauty our state has to offer.

“I would love to see the Tucson International Airport have a big sign,” Dr. Curiel says. What would it say? “Welcome to Arizona. Put on Sunscreen and Wear Your Hat. Don’t Let Skin Cancer Be Your Souvenir!”